Paper by Leah Hunnewell

Irish Labour Internationalism: The ITUC’s transnational relationships 1900-1920

The digitisation of the Irish Trade Union Congress (ITUC) records marks an important development in Ireland’s economic, social, political and cultural history. These records include information on labour’s forgotten men and women, such as Elizabeth McCaughey, ten year delegate for the Belfast Textile or Operative Union, John McCarthy, seven year Kilkenny Trades Council representative, and countless others who have been forgotten in a nation which lamentably suffers from the lack of a National Dictionary of Labour Biographies1. While fruitful labour studies have been conducted in areas such as Waterford, Kilkenny, Limerick, and Kerry, many regional studies of labour remain unwritten2. These records move us closer to understanding the experiences of these neglected areas. However, the collection not only addresses problems faced in the workplace, but also socio-economic issues as well. Topics such as the feeding of school children, the establishment of adult technical education, and even questions about the merits of secular education in Ireland all feature within the ITUC debates. Nevertheless, while each of these areas explore neglected bottom-up historical narratives within a critical time in Ireland’s development, these records also offer valuable insight into how the Irish labour movement interacted with outside nations. With current historiography shifting towards a more transnational scope, I wish to use this opportunity to explore some of these concepts as a means of demonstrating how these records capture part of Ireland’s relationship to the outside world.

The ITUC regularly maintained formal links with other national labour movements. These transnational interactions expose the complex and, at times, paradoxical ways in which members of the ITUC professed both internationalist and nationalist ideology. These exchanges raise questions about why particular transnational connections are forged and others are not. Furthermore, they expose the often delicate dynamics of transnational relationships constructed within an imperial context. Using the ITUC records as the core, this paper will analyse the transnational exchanges that occurred between fraternal labour delegates and foreign political leaders during the years 1901-1925.

Speaking as a representative of the British Labour Representational Committee (LRC), Scottish labour leader Kier Hardie, addressed the 1903 Newry ITUC with a strong message of international solidarity. Hardie focused on the power of international labour consciousness to overcome the core obstacles dividing the Irish labour movement:

when the labour members came from Ireland, as they would come, they would work together outside all the political differences that had weakened their ranks in the past, realising that they had one common interest, which was greater than national feeling, greater than religious difference, the principle of seeking to uplift the people to whom they belonged, and to make their life more worth living than it had been in the past.3

The inspirational message had a motive. Hardie, along with his LRC partner Ramsay MacDonald, hoped to transform the ITUC into a supportive branch of the British Independent Labour Party (ILP). In fact, the ILP, as early as 1893, had been campaigning in Belfast, Waterford and Dublin, and had managed to establish fleeting branches in each city.4 However, outside of Belfast where early support was maintained through the work of the city’s leading socialists, William Knox and William Walker, the ILP failed to sustain a significant presence in Ireland. By 1903, Hardie clearly had renewed hope for a politicised labour movement that would stretch across the British Isles. ITUC delegates were aware of Hardie’s underlying ambitions. The warm thanks and cordial applause he received only masked the fact that some ITUC delegates did not support Hardie’s plan. Many labour leaders still backed the Irish Parliamentary Party, while others maintained a long-term plan of transforming Irish labour into an independent political party; however the LRC certainly had its supporters within the ITUC as well. The ‘common interests’ of the working classes, in this instance, were not exactly common and they were certainly not ‘greater than national feeling’. Nevertheless, Hardie’s message captured some of the obstacles that beset a nation attempting to challenge its colonial identity, while simultaneously maintaining its belief in the international cause of labour.

ITUC leaders across the political spectrum justified their decision to establish their own national movement on the grounds that the Irish working classes did not face the same conditions as their English counterparts. This reality meant it was not practical for Irish leaders to rely exclusively on wider British organisations to advance the cause of Irish labour. In his 1901 Presidential address, Belfast delegate Alexander Bowman, explained this concept:

Two bodies or communities cannot satisfactorily progress side by side except [when] their starting point be [is] identical and their rate of progress equal. When we contrast the industrial position of the richer island with that of the poorer—the position of Great Britain with that of Ireland—we must recognise that these countries can make best progress by each going forward from its own standpoint and at its own rate.5

The inequality that Bowman referenced was quite clear. Irish wages remained significantly below those of English workers while a significant portion of the Irish workforce still remained unorganised. Adding to this predicament was the waning of Irish representation to the British Trade Union Congress (TUC) from the 1890s into the 1900s. ITUC delegations to the British TUC decreased from 31 delegates at the 1893 Belfast TUC to merely six representatives at the 1901 Swansea TUC6. ITUC Vice President, John Simmons, blamed this decline on the ‘remote places’ where England chose to hold TUC meetings, which resulted in the Irish ‘practically being denied representation.’7 Even Irish delegates who were able to attend fell short of an all island representative pool. Irish delegates most often represented the faces of traditional trade unions and came largely from urban centres of Dublin and Belfast.

Even Belfast leaders, who maintained the strongest political ties to the British system, felt an Irish Trades Union Congress could better serve Ireland’s industrial needs. Belfast labour leadership, with its strong strand of unionist labour, was confident that it could control the break and ensure that the ITUC became a solid branch of the wider British movement. The advanced stages of Belfast industry and the city’s concentrated workforce further convinced Belfast leaders the city could attain the centre position of the Irish national movement.8 It was believed the old guard of British trade unionism would lead the way for Irish trade unionism as well. Since Belfast sent the most Irish delegates to the British TUC, past evidence indicated the city would have the most representatives in the ITUC as well. It was not necessarily a radical new departure, rather it was Irish labour within the British movement.

The beginnings of the Irish Congress followed this pattern. The original executive members of the ITUC were largely Dublin and Belfast based, and all served as delegates to the British TUC.9 Dublin based union delegates made up 39.96% of the total delegation during the years 1901-1917. Across the entire span of this collection, only 23% of the members of the National Executive represented areas outside of Dublin and Belfast. Even participation within the congress reflected the Dublin/Belfast dynamic. Out of the 26 motions raised on the first day of the Congress during the years 1901, 1905, and 1910, 13 were put forth by Dublin delegates and 10 by Belfast representatives.10

British TUC leaders, sympathetic to the problems Ireland faced and possibly more consumed by the emerging political power of British Labour, remained supportive of the Irish venture.11 From their perspective, the promotion of Irish labourism in Ireland, by the Irish, alleviated the burden on the British TUC leadership. Irish labour’s increased autonomy proved to be less than revolutionary in these early days. The ITUC simply mirrored TUC strategy, while still asserting its right to independence. Dermot Keogh has claimed that the limited vision of the ITUC during the early years reflected a ‘potential for division which lurked beneath the surface.’12 The practices and patterns of the ITUC’s transnational relationships suggest an alternative interpretation, however, and indicate that Ireland’s colonial identity penetrated the mindset of Irish labour leaders so significantly that it affected their ability to search for labour networks beyond the British Isles. This interpretation is supported by the work of Emmet O’Connor, who has described the ITUC’s early policies as ‘bizarre self-denial’ or ‘mental colonisation.’13 O’Connor argues that the ITUC’s early emphasis on industrial expansion, in line with TUC policy, kept the ITUC’s influence at a minimum in a society where rural concerns dominated national politics. This Anglo-shaped vision of labour ultimately served as a counter-revolutionary force to the radical vision that of some the ITUC’s early leaders maintained. This state of mental colonisation prevented the ITUC from establishing fruitful trade union connections better suited to the Irish experience and instead kept Irish labour inherently tied to the British Empire.

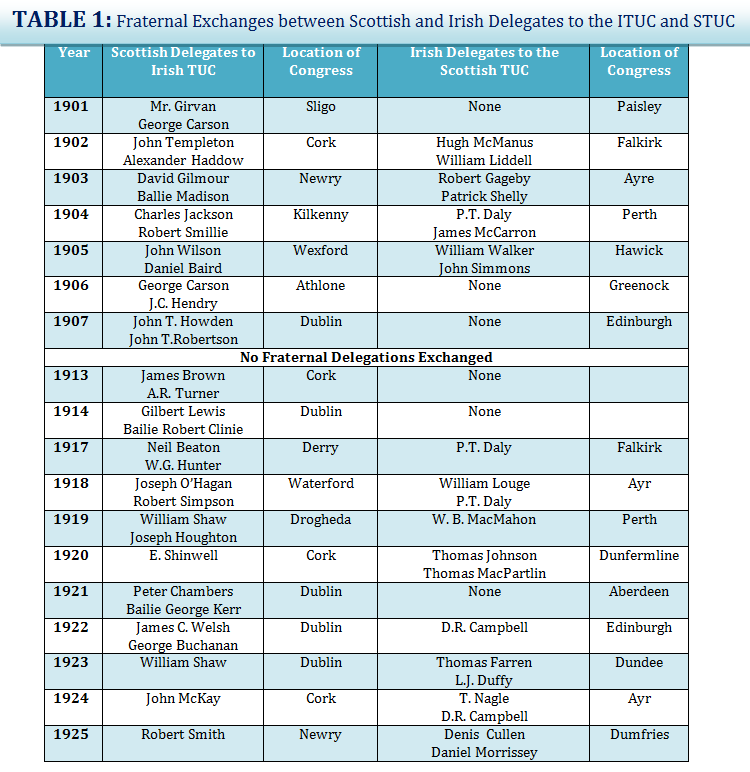

After its development, the ITUC soon turned to its closest neighbour, Scotland, which had created its own Scottish Trade Union Congress (STUC) in 1897. Both groups saw themselves as the underrepresented partners in the British labour movement and used this image to construct a shared identity between the two congresses. As Table 1 demonstrates, the exchange of fraternal delegations with Scotland soon became routine practice. These exchanges served initially to inform each body about the progress and major goals established by each congress. However, these visits were also accompanied by formal dinners, public excursions and exchanges of symbolic gifts.14 While some Irish delegates originally held reservations about the usefulness of these ‘junkets’, by 1904, leaders acknowledged that these exchanges served an important role in ‘fostering goodwill’.15 Such ceremonies eventually became the clearest manifestation of transnational labour networks that arose out of common social, economic, and political concerns.

Many believed that fraternal exchanges should work directly toward practical international political goals, albeit within the wider British political system. Scottish delegate, George Carson, called for the development of a ‘common policy’ between the two movements.16 However, even with similar political positions and a shared language of labour, finding points of common-ground between the Scottish and Irish labour movements proved difficult. Despite the assertion of John Wilson, a Scottish delegate, that the ‘interests of the two nations were identical’ most leaders acknowledged that the very different nature of each national movement kept them focused on different goals.17 Tangible evidence of this was that in the same year Wilson made his proclamation, the Irish delegation to the STUC returned with a report calling for the termination of these exchanges. The leaders claimed that due to the financial state of the ITUC, it was better to focus on building the movement in Ireland.18 Fraternal delegations were expensive, costing an average of £8 3s. But with an average budget surplus of £65 7s between 1901 and 1905, they were certainly not an unmanageable burden for the ITUC.19 It was more than budgetary concerns keeping the two nations apart.

In the same year as the call to terminate these exchanges, the Dublin Typographical Society complained about reciprocal trade unionism, which saw members of English and Scottish societies replacing Dublin Typographical Society members at jobs in Ireland. Dublin Typographical Society delegate, John Lyons, went as far as suggesting that fraternal greetings not be sent to the Scottish Congress, claiming that the Scottish were not being ‘fraternal to Ireland’. James McCarron, reminded Lyons that fraternal greetings were ‘a friendly act between trade unions in two countries and had nothing to do with any dispute between societies’. Nevertheless, the Congress still decided to send separate messages to the secretaries of the Scottish and English Typographical Societies and the Scottish and English Trades Congresses that called on the co-operation of societies against acts of reciprocal trade unionism.20

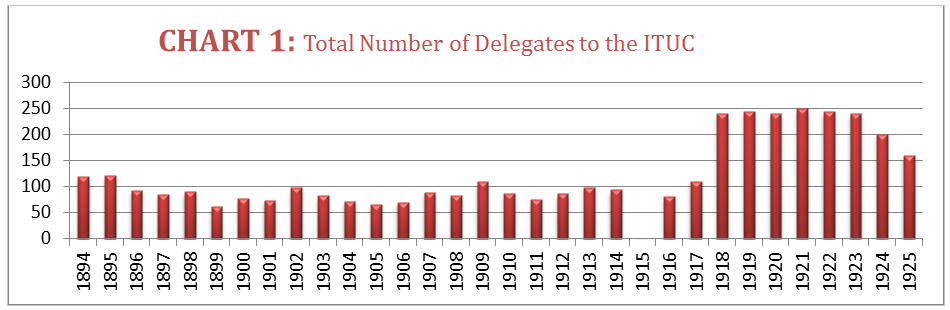

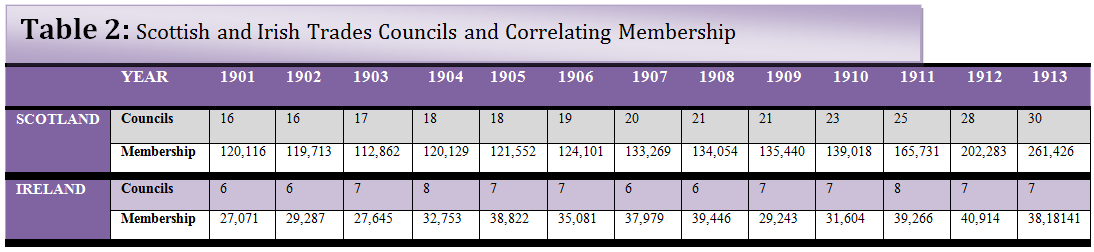

Alongside these tensions caused by transient workforces, a number of other practical issues distanced the Irish and Scottish trade union movements. The Scottish movement was larger and further developed than the Irish Congress. In 1903, the STUC had 129 delegates representing 130,000 union members, while the ITUC had 89 delegates representing 70,692 members. As chart 1 demonstrates, the ITUC did not claim such numbers until 1918.

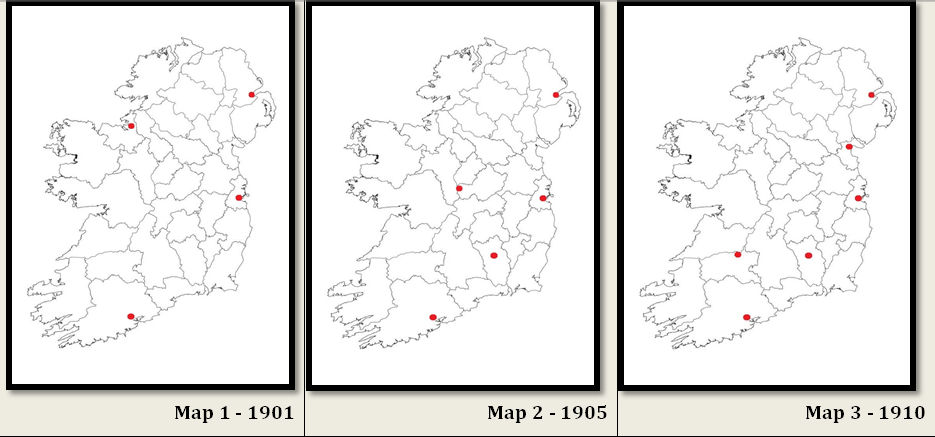

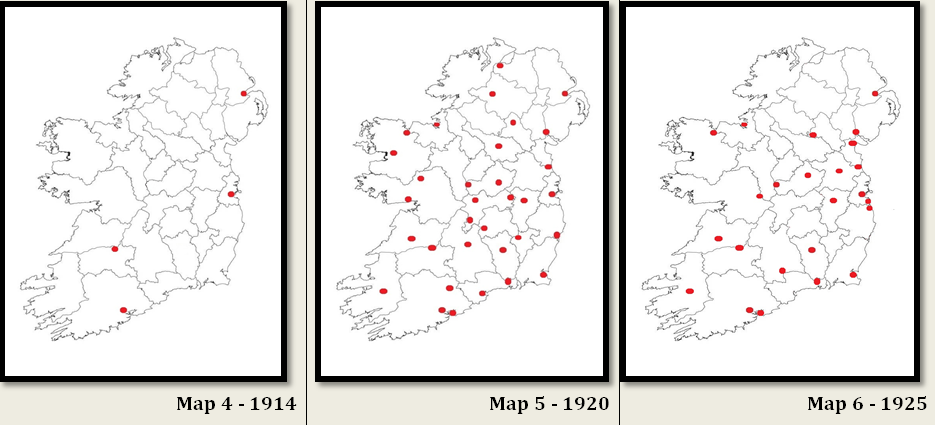

Another differing element was in local trade union representation. As Table 2 demonstrates, unlike Scotland, Irish industrial centres did not maintain regular trades councils.21 Even some cities with trades councils either could not or did not send delegations to the ITUC. In 1914, only four cities – Dublin, Belfast, Limerick and Cork- sent independent trades councils to the ITUC. As can be seen from maps 1-6, this is a decrease from six in 1910.22

Maps 1-6: Trades and Labour Councils Represented at the ITUC, 1901-1925

Even where these Irish trades councils existed, they faced a number of obstacles in promoting their agendas. Between 1904 and 1905, Belfast was the only trades councils that ran a monthly labour organ, The Belfast Labour Chronicle, which survived largely through the continued support of William Walker. It was not until 1909 that the Dublin Trades Council would try a similar venture with the Dublin Trade and Labour Journal. Prior to these developments, the lack of propagandist material hindered the expansion of the national movement and kept the ITUC dependent on British or Scottish organs to fill the void. The only alternative was the nationalist or regional press, which limited the ability of Irish labour to develop its own distinct voice and identity outside of Irish national politics.

After a tied vote to revive the Scottish-Irish TUC exchange was defeated by the casting vote of ITUC president James McCarron in 1907, the ITUC failed to send another delegation to the STUC until 1917.23 The ITUC‘s self-imposed isolation during these years reflected the transformation the ITUC was undertaking. The years 1908-1913 saw an increase in nationalist rhetoric that heightened tensions in the Congress and made for a less welcoming environment for outsiders. James Larkin’s establishment of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU) posed a severe challenge to the Congress. Questions about the validity of the ITGWU took a toll on the 1909 and 1910 Congresses. Older leaders, fearing a loss of power and the looming threat of the new industrial unionism that Larkin’s union represented, went on the attack both within and outside of the Congress. Former ITUC treasurer (1904-1908), president (1909) and Irish Socialist Republican Party secretary, Edward Stewart, launched a visceral attack on the ‘Larkinite circle’ as he saw it, represented by James Connolly, Patrick T. Daly, William O’Brien, and Michael O’Lehane. In his pamphlet, The History of Larkinism, Stewart used nationalist prejudices in an attempt to curb Larkin’s influence within the ITUC. Stewart claimed Larkin was a ‘foreign adventurer from the slum recesses of probably some clog-wearing Lanacashire town’ while adding that Michael O’Lehane was a fake Sinn Féiner who added the O to his name to sound more nationalist.24

Rather than searching for the moral high ground, Larkin and his supporters fired back with their own increasingly nationalist rhetoric. In 1911, when debating the merits of creating an Irish Labour Party, Larkin was reported as declaring:

When dealing with Labour questions, let the Congress not be humbugged by men who talked about internationalism. The Labour Party in the United States, Canada, or Australia, would never allow any English Labour Party to manage their affairs. (applause) Why should they in Ireland? He declined to allow any Scotch, English, or Welsh party to come into this country to interfere with the Irish workers (applause).25

Despite reminders from opponents that Larkin was one of those Englishmen who arrived in Ireland working for a British union, Larkin refused to concede any place to outside influence in the Irish labour movement. Michael O’Lehane attempted to cool the tone claiming that he identified more as a ‘cosmopolitan,’ yet he still asserted that there could be no internationalism without nationalism first.26

Amidst this increasingly polarising dynamic, the ITUC did attempt to refocus its ‘shared labour identity’ through transnational links that steered clear of the British Empire and syndicalism. The compromise was the American Federation of Labor (AFL). As a federation, the AFL maintained an illusion of openness and progress that was just enough to appease both sides. The AFL had regularly shared fraternal delegations with the British TUC since 1894, and, in 1909, it selected its leader, Samuel Gompers, to serve as the British TUC delegate. The visit was part of a wider European study conducted by Gompers on behalf of the union’s paper, The American Federationist. Coordinating with the Dublin Trades Council, the ITUC established a delegation consisting of E.W Stewart, Mary Galway, Henry Rochford, and E.L. Richardson to greet Gompers alongside William O’Brien, Michael O’Lehane, and P.T. Daly. Despite Gompers’ praise of Irish labour’s ability to ‘move past political divides’, the healing venture did not go as planned.27 Tensions still reigned through the ITUC, with Larkin complaining that figures like Mary Galway and E. W. Stewart were out to get him.28 Plans to raise the issue of independent labour politics in Ireland made Gompers’ visit seem all but ceremonial, since the AFL took a firm stand on the political question; they were not a political party and certainly not a socialist one. ITGWU sympathisers and ITUC international socialists were not looking at the AFL for guidance, but they were not reaching any further either. Figures such as James Larkin, James Connolly, Thomas Johnson and William O’Brien who were Second International socialists advocated for the spirit of internationalism, but defending outside attacks from old unionists, like the one issued by E.W. Stewart, prevented them from asserting unadulterated views of internationalism. As a result, Irish nationalism came first with internationalism as a long-term ideal.

Unafraid of a challenge, Belfast organiser, Mary Galway, decided to open the 1910 Clonmel Congress by stating she wished ‘as a woman’ to extend sympathy to Queen Alexandra on her recent bereavement. She found herself interrupted by William O’Brien who shouted, ‘Humbug!’ which was met with a round of applause. E.W. Stewart took the opportunity to reprimand O’Brien, warning him he needed to ‘respect a lady.’29 The simmering tensions flared again when Walker challenged the move toward an Irish Labour Party by using Scotland as an example of what not to do. He asserted that Scottish attempts to form an independent Scottish Labour Party had failed, and the movement now served as a complementary branch of the British Labour Party. Ireland, he warned, should not go down the same path, unless they wanted to undercut internationalism.30 However, in spite of this opposition, resolutions favouring both the formation of an Irish Federation of Labour and an Irish Independent Labour Party were passed and Clonmel opened the window to a new venture for the ITUC.

Victory at Clonmel came at a cost. Belfast delegates resolved not to attend the 1913 Congress as a form of protest.31 With the opposition gone, the Scottish delegation returned in 1913 with a clear understanding that they were dealing with a new ITUC. Scottish delegate A.R. Turner, praised the way the Scottish Labour Party became a branch of the English Labour party, but refused to elaborate on whether Ireland should have its own Irish Labour Party.32 Instead the Scottish delegation avoided any direct political dialogue. With the potential for coordinated political action gone, delegates instead used the exchange as a type of public diplomacy to generate support for the Labour Party in Scotland within Irish communities. Rather than talking about political plans, delegates played up Celtic links and praised the Irish Diaspora in Scotland as a revolutionary force of Scottish labour, focusing particularly on the Clyde. In 1918, Scottish delegate Joseph O’Hagan boasted his Irish credentials, while claiming the British authorities were doing what they could to ‘raise a racial war’ between the Scottish and Irish communities.33 This fiery racial message was intended to foment a shared concept of persecution and promote labour radicalism in Scotland, a far cry from the practical strides leaders initially sought.

In 1919, the ITUC at last made a concerted effort to move away from its Anglo-centrism by sending an independent delegation to the International Labour and Socialist Conference. At Berne, the ITUC measured its historical internationalism through the connections of Ireland’s socialist movements, rather than the labour movement. It pointed to the links of the Socialist Party of Ireland with the American Socialist Labour Party, an exchange which was ceremonial at best.34 Nevertheless, leaders admitted that ITUC internationalism consisted of relations with England and Scotland and further acknowledged that 1912-14 was a ‘period of peculiarly militant and class-conscious’ activity that ‘imposed such a strain upon the Irish movement that the development of its relations with the workers of the Continent was retarded.’35 The conceit was accompanied by a promise of increased internationalism, but the 1920 ITUC did not support such a measure.

Second International men, some of the ITUC’s earlier radicals, were now in opposition to the growing support of the Third International. Drogheda Trades Council delegate, Eamonn Rooney’ s resolution calling on the ITUC to withdraw immediately from the Second International cited British attempts to challenge the Soviet Union. The debate culminated with Thomas Johnson boasting: ‘Let the Internationale come to us and say they are prepared to follow our lead, for we are doing things that they are only preaching about (applause).’36 The result was that internationalism, even at its height, resulted in Ireland looking inward instead of out, and again asserting its connection to the British movement. Ultimately, the decision to turn away from Berne captured Irish labour’s limited commitment to (the) international ideal.

With the failures at Berne, the ITUC returned to its fraternal and comfortable relationship with Scotland. Attempting to move beyond its Atlantic connections, the ITUC invited the Indian Workers’ and Welfare League to send fraternal delegates from 1919-1923. Dr. Bhat, S. Sakllatvala and D. D. Khanna each served as representatives and in 1919 the ITUC turned a speech by Dr. Bhat into a pamphlet, which it sold during the 1919 labour struggles. The speech served well as a propaganda piece, but it was clearly meant first and foremost to serve Irish needs. The image of Indian labourers working for an average income of less than £2 a year in atrocious sanitary conditions boasted the importance of international class-consciousness, but it maintained internationalism within a colonial sphere. International labour protest equated to protest against the British capitalist classes.37 Once again, the ITUC’s ostensible internationalism proved to be limited and unable to escape its primary concerns with the British Empire.

Transnational relationships during these early years were more symbolic than practical. While it is true the ITUC’s limited funding had a certain impact on its development, its Anglo-centric view of the world was the primary reason that it failed to explore options beyond the British Isles. The result was that while trying to escape the constraints of colonialism through labour internationalism, the ITUC only confirmed the significant impact colonialism had on the movement. Ireland’s lack of innovative internationalism set the nation on a potentially misguided course to British-style labour politics, which ultimately hindered the development of the labour movement. The real problem was that the ITUC’s vision of what labour internationalism was only stretched far enough to get them across the Irish Sea.

1. Saothar, the journal of the Irish Labour Historical Society, comes closest to addressing this issue with its reoccurring feature entitled, ‘Labour Lives’ detailing biographies of a number of the more active individuals within the labour movement.

2. For examples of these works please see Marilyn Silverman, An Irish working class: explorations in political economy and hegemony, 1800-1950 (London, 2001); ); Emmet O’Connor, A labour history of Waterford (Waterford, 1989); or Emmet O’Connor, Derry Labour in the Age of agitations, 1889-1923 (Dublin, 2014); or Thomas Neil Crean, ‘The Labour movement in Kerry and Limerick, 1914-21’ (PhD thesis, Trinity College Dublin: Thesis 3883, Oct 1995).

3. ITUC 1903, p 19.

4. John Boyle, The Irish labour movement in the nineteenth century (Washington D.C., 1988), pp. 184-6.

5. ITUC 1901, p 8.

6. Of the 31 delegates to the 1893 Congress only four came from Dublin, two of whom (John Simmons and George Leahy) served as delegates for the Dublin Trades Council, while the other two served as delegates for Typographical Society of Dublin and the House Painters Trade Union. All other delegates were Belfast based. The TUC Annual Congress Reports 1893 and 1901 available online at www.unionhistory.info/reports.

7. ITUC 1901, p 3.

8. By 1891, 42.2% of Belfast labour force belonged to the manufacturing sector, placing the city far above the 10.5% for Ireland’s overall population. Early advancements in organising labour, particularly in the shipyards, made the city, a leading urban centre for organised labour. For further information please see, Belfast labour John Lynch, ‘The Belfast Shipyards and the Industrial Working Class’ in Francis Devine, Fintan Lane and Naimh Purseil (eds) Essays in Irish Labour History: A festschrift for Elizabeth and John W. Boyle (Dublin, 2008), p. 135.

9. This concept was emphasised by Charles McCarthy, who, in the open of his work, described the history of the ITUC as a tale of two cities: Dublin and Belfast. Charles McCarthy, Trade Unions in Ireland, 1894-1960 (Dublin, 1977), p 1.

10. ITUC 1905,1910,1915.

11. John Boyle, The Irish Labour Movement in the Nineteenth Century, p 233.

12. Dermot Keogh, ‘Foundation and Early Years of the Irish TUC 1894-1912’ in Donal Nevin (ed), Trade Union Century (Dublin, 1994), pp 21-22.

13. Emmet O’Connor, A Labour History of Ireland, 1824-2000 (Dublin, 2011), p 63.

14. The most were iconic gifts of national literature. For example in 1918, the ITUC presented to the Scottish delegation The Spirit of the Nation, while the STUC presented two volumes of Robert Burns poetry. ITUC 1918, pp. 56-7.

15. ITUC 1904, p 37.

16. ITUC 1901, p 40.

17. ITUC 1905, p 39.

18. Ibid, p 37.

19. ITUC 1901-1905.

20. ITUC 1905, p 36, ibid, pp. 43-4.

21. Numbers and Membership to Trades Councils, 1899-1913, Seventeenth Abstract of Labour Statistics of the United Kingdom, British Parliamentary Papers , Board of Trade (CD733), pp. 224-225.

22. These maps represent five year snapshots of ITUC trades and labour council delegations. Due to the absence of a council in the year 1915, 1914 was used in its place.

23. ITUC, 1907, p 55.

24. E.W. Stewart, The History of Larkinism, (P.R.O.N.I. D3983/PTE 11/ACC 1993).

25. ITUC 1911, p 40.

26. Ibid, p 41.

27. The American Federationist, September 1909.

28. Edward MacLysaght (ed), Forth the banners go: reminisces of William O’Brien (Dublin, 1969), p 50.

29. ITUC 1910, p 14.

30. Ibid, p. 48

31. O’Connor, A labour history of Ireland, p 76.

32. ITUC, 1913, p. 49

33. ITUC, 1918, PP. 56

34. Due to the Connolly’s famous feud with American Socialist Labour Party leader De Leon in 1904, the socialist movement in Ireland slowly began to pull away from its ties to the Socialist Labour Party and instead established minor ties to the Socialist Party of America. For further information on this split, please see James A. Stevenson, ‘Clashing Personalities: James Connolly and Daniel De Leon, 1896-1909’ in Éire-Ireland (Fall 1990), pp. 19-36.

35. ITUC Berne 1919, p 24.

36. ITUC, 1920, p 108.

37. ITUC , 1919 p 90.

—

Leah Hunnewell is an Irish Research Council funded PhD student at Trinity College Dublin. Her research explores Irish working class culture and its influence on radical politics from 1889 to 1917. Particular emphasis is drawn on the use of national, religious, and racial language within socialist propaganda. With the background of the Second International, the research explores connections to other Atlantic movements as a means of contextualising the transnational experiences of diaspora working class communities.